CAMP LIFE

The Indian truthfully observes: “White man make heap big fire; keep far off. Indian make little fire; get close. All same.” The small fire does best in the circular tepee tent, made of canvas or leather, in use on the plains. The tepee is quite an institution, but it is generally as full of smoke as a kitchen chimney, and for that reason cannot truthfully be recommended. In theory, the smoke should all pass out of the opening in the top.

By using no second skin and carefully excluding all air from around the lower rim of the tepee, it will become an admirable place to cure hams, fish, etc., by the original smoke-dried process. The Scripture declares that he that tarrieth over the wine cup has red eyes next morning, and so has he that sleeps in a smoky tepee. Properly made, however, the tepee is the thing where wood is scarce.

Some original spirits are said to have started for Dawson City, N.W.T., a few years ago with bicycles and push carts. If these means of transport had sufficed, the world would have learnt something, as heretofore a canoe and a sturdy pair of legs were supposed to help the wayfarer in that region better than anything else. That is in summer; in winter, the dog-train is the quickest mode of travel. In the western states and in British Columbia pack horses or mules do the most of the prospector’s freighting, and in the far north he either carries his outfit on his back or else transports it by canoe in summer, or by dog-train after the rivers have frozen.

![]()

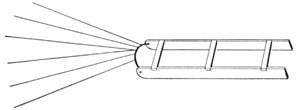

HUDSON’S BAY DOG SLED

No amount of written instructions will teach a man to throw a diamond hitch, or handle a canoe in swift water. A lesson or two from an expert will, however, set his thoughts in the right direction, and in time he may become proficient. Canoeing, freighting and chopping are three things that are best begun in boyhood; no one ever yet became marvelously proficient in any one of them that began after reaching adult age.

YUKON SLED AND HARNESS

Dog teams are made up of from three to six dogs; a full-sized team dragging a load of 200 pounds forty miles a day for a week at a time. In the Hudson Bay region the dogs are harnessed one behind the other, but on the Yukon each pulls by a separate trace, and the team spreads out like a fan when at work.

After Christmas the snow-shoe is generally a necessity in the north. Without “paddles” on the feet the explorer could hardly make his way through the woods, while with them on he sails along gayly, making a bee-line over frozen lake and water courses, and taking windfalls and down timber in his stride. The shoe in vogue in the forest is short and almost round, and flat, while that of the plains is very long, upturned at the toe, and narrow. There is a reason for these modifications, as the tyro will soon find out should he substitute the one for the other in the native habitat of either. But the loop by which the shoe is fastened on the foot is always the same. The string is made of moose hide; stretched, and greased before use. Caribou, or reindeer hide, makes the best filling, but horse or bull hide will do at a pinch. The frame is usually of ground ash, or some other tough, hard wood.

A camp kit of cooking utensils often begins and ends with a frying-pan and tin kettle. Certainly when traveling light, these things should be the last to go, as with them all things are possible, even to amalgamating and retorting the precious metals. The frying-pan must have a socket instead of a long handle, as the latter may be cut from a bush at any time. A low, broad kettle boils in less time than a deep, narrow one of the same cubic capacity.

All provisions should be kept in canvas bags. Matches in a leather case or safe, or in a corked bottle. Blankets are never kicked off if sewn up at foot and side into a sleeping bag.

The existence of the prospector being passed in regions where the so-called benefits of civilization have not penetrated, he is generally a healthy, happy, hopeful man. Especially, hopeful. I do not remember ever meeting one that was not brimful of expectation and trust in the future. Possibly prospectors that have become pessimistic drop out of the ranks.

Now the man who elects to dwell with nature has only himself to thank if he does not like his lodgings. He can be comfortable or wretched, according to his knowledge of woodcraft and wilderness residence.

Whereas the tyro starts out with the avowed intention of “roughing it,” the veteran is particularly careful to take matters as smoothly as he may, being well assured that in any case there will be enough inevitable discomfort in his lot to satisfy any reasonable craving. It is just the same in other walks of life; the sailor, the trapper and the soldier each learns to look after his own comfort and to seize every opportunity of making life as pleasant as possible.

The three prime wants are food, clothing and shelter, and their importance is in the order named. Now, food is something that is painfully scarce in many parts of the world, and one of the great problems of wilderness travel is to provide transport for the supplies that must be carried from civilization. A rigorous northern climate necessitates a large consumption of strong, heat-producing food, while in the tropics the explorer gets along very comfortably with rice or an occasional skinny fowl, with plantains for dessert, and plenty of boiled and filtered water. Compare such a diet with that of Nansen, the arctic explorer! He and his companion lived and waxed fat on a diet of lean bear’s meat three times a day, washed down by draughts of melted snow water. Moreover, although government expeditions, provided with every canned and potted luxury the stores contain, have suffered the ravages of scurvy, these two adventurous Norwegians, living on the food their rifles had provided, did not know what sickness meant.

Other travelers have found that they fared better by copying to some extent the manner and customs of the natives. Fat seal blubber gives wonderful resisting power against cold, it is said; while a mild, unstimulating diet of rice suits the liver better under the Equator than the Bass ale and roast beef galore.

On this continent the working man found out long ago that pork and beans suits him nicely. The lumberman says: “It sticks to the ribs,” by which robust, if not classical, phrase he means that he can chop longer without feeling hungry on pork and beans than on almost any other food. The laborer having found by experience that the side of a pig and a sack of beans was a good combination to have in the larder, the man of science after a couple of hundred years or so of deliberation confirms the discovery by announcing that the flesh of a swine mixed with the fruit of the bean contains all the carbo-hydrates, etc., necessary to sustain life. The moral of all this is that pork and beans must not be forgotten when outfitting. A few other things being desirable, the following list may be consulted to advantage by the prospective prospector. This list should suffice for feeding one man for 12 months:

Sugar 75 pounds.

Apples (evaporated) 50 pounds.

Salt 25 pounds.

Salt pork 212 pounds.

Pepper 1 pound.

Condensed milk 1 case.

Flour 2 barrels.

Candles 1 box.

Matches 12 boxes.

Soap 1 doz. bars.

Tea 1/2 case.

Beans 200 pounds.

The dictates of fashion being unheard on the mountain side, and beneath the pines, dress resolves itself into a mere question of warmth and comfort. Cut is of importance truly, but only insomuch as it allows free play to the limbs; to the arms in digging, and to the legs in climbing the stiff side of a canyon. Home-spun, heavy tanned duck, corduroy or moleskin, and flannel underclothing should be the mainstays of a miner’s wardrobe. Rubber boots and slickers are also necessary to his comfort, while for winter use a heavy Mackinaw overcoat, or even fur, for the extreme north, is advisable. When actually at work the miner is more often in his shirt sleeves than not, and cold indeed must the day be if an old woodsman is caught traveling through the forest with his burly form encased in furs. For arctic conditions akin to those found on the upper Yukon an outfit such as the following should be chosen:

2 heavy knitted undershirts.

2 flannel shirts.

6 pairs worsted socks.

2 pairs overstockings.

1 pair miner's boots.

1 pair gum boots.

2 pairs moccasins.

1 suit homespun.

1 horsehide jacket.

1 pair moleskin trousers.

1 broad-brimmed felt hat.

1 fur cap.

1 Mackinaw overcoat.

2 pairs flannel mitts.

1 pair fur mitts.

1 muffler.

1 suit oil slickers.

2 pairs blankets.

In cold weather the feet, fingers and face require the most care. The first should be stowed into two pairs of wool socks, and a long pair of knee-high oversocks be drawn over these. Boots must be replaced by moccasins. A pair of thick worsted mitts, and a pair of leather mitts outside, keep the hands warm enough even at 20 degrees below zero. At 50 degrees below put on an extra pair–or go home until the weather moderates.

The favorite style of architecture in the wilderness is neither Doric nor the Gothic nor yet the Renaissance. It is called the dugout. The beauty of the dugout is its extreme simplicity. A hole in the side of a dry bank, a few sods or logs for roof, and there you have it. A veteran miner goes to earth as easily as a rabbit, and, like bunny, is never at a loss for an habitation.

Next to the dugout the log cabin deserves mention, while the wattle and daub or ‘dobe certainly secures third honors. The only drawback to the pre-eminence of the log cabin is that to make it you must have logs–just as the cook always insists on pigeons before she makes pigeon pie–and logs are in some districts only known as museum specimens. Now, the dugout or the 'dobe only require a gravel bank, or one of those deposits of argilite that the vulgar persist in calling clay; were it not for this fatal ease of getting, every miner and prospector would doubtless prefer living in a snug log hut, there to await in peace, comfort, and dignity the arrival of the representative of the “English syndicate” to whom he is destined to sell his claim.

Napoleon found, after fighting his way across Europe and back again, that his troops were more healthy bivouacking in the open than sheltered in tents. In truth, the tent is a very uncomfortable and unhealthy make-shift; cold, hot, and damp, by turns, and often badly ventilated. A simple lean-to shelter, and a roaring fire are infinitely preferable where wood is abundant. But it takes a lot of wood to keep a bivouac warm on a winter’s night; as much perhaps as would feed a fair-sized family furnace for a month.

The trappers' fire is a most regal blaze. Two back logs; a pair of “hand junks” and a “forestick” are the foundation upon which the structure is reared, but the edifice itself often consumes a tall, full-limbed rock maple, or a stately birch between the setting of the sun and the rising of the same. There are three ways of making a fire; the first is suited for a “wooden” country; the second is used by “Lo,” and other prairie travelers, where fuel is scarce.

If overtaken by storm in any wild northern region, do as the animals and Indians do under like circumstances: seek the nearest shelter and lie close until the weather has moderated. The secret is to conserve your energy, not to fritter it away fighting a power against which you may make no real headway. A shallow, brush-lined gully; the lea of a bank, or small clump of trees; these and other seemingly slight protections sometimes mean life instead of death. The experienced woodsman never leaves camp without matches in his pocket; and in winter he carries a few pieces of dry birch bark in the bosom of his hunting shirt, as he knows how vitally necessary it is on occasions to be able to kindle a blaze at very short notice.

A tent should never be pitched loosely, as no matter how fine the evening the weather ere morning may be tempestuous in the extreme, and the unpleasantness of having a tent come down about one’s ears in the dark must be experienced to be realized. Also, never pitch a tent with the doorway toward the northwest in winter, because that is the quarter from which comes the cold.

In summer, from June until mid-August, the mosquito, the black fly and the midge or sand fly, make life a burden in the north. The best remedy for the mosquito and black fly is a mixture of tar and olive oil, of the consistency of cream, rubbed on all exposed parts of the person. A dark green veil will also keep the insect pests out of the eyes, mouth and ears, and in winter is better than snow goggles to avert blindness. But, unfortunately, it interferes with the enjoyment of the pipe, and hence is not in much favor with woodsmen.

To make good bread it is not necessary to take either yeast cakes or mixing pan into the wilderness. An old hand thinks himself rich with a few pounds of flour in his sack, and soon has a batch of bread baking that would turn many a housewife green with envy. He proceeds in this fashion: A visit to the nearest hardwood ridge shows him a green parasitic lichen growing on the bark of the maples (lungwort). Some of this he gathers, and steeps it over night in warm water near the embers. In the morning he mixes his flour into a paste with this decoction, using the bag as a pan. The dough is next covered with a cloth and set in a warm corner to rise; a few hours later it is re-kneaded and baked. The result should be delicious bread. Some of the leaven, or raised dough, may be kept, and will suffice for the next batch of bread, and so on ad infinitum.

Making bed takes longer in camp than in the city, but the result is just as satisfactory. Nothing more comforting than a couch of fir boughs has been devised by man. Choosing a level spot the woodsman cuts several armfuls of the feathery tips of the fir balsam. These he places in layers like shingles on a roof, beginning at the foot and laying the butt of each bough toward the head. If sufficiently deep, say a couple of feet or so, such a bed will be soft and elastic for a night or two, when it will require re-laying. Fragrant it always is, with the delicious aroma of the fir balsam.

The white man stretches himself instinctively feet to the fire; the Indian just as instinctively reclines with his side to it–and his way is the most philosophical.

Strange as it may seem, the greatest danger the wanderer runs is on his return to civilization. Land surveyors, engineers, and others whose work calls them into camp for months at a stretch, dread their first night in a feather bed. They find by experience that they are lucky if they escape with nothing more serious than a heavy cold. Hot, stuffy air, and poor ventilation cause the trouble. Leaving the window wide open will almost always prevent these evil consequences, and allow the constitution to become once more tolerant of a lack of oxygen. In the wilderness, notwithstanding, wet, cold, and exposure, such ills as consumption, pneumonia, bronchitis, etc., are unheard of.

Boat building and net making are two arts that the prospector will do well to master. A few weeks passed in a building yard, and a half dozen lessons from an old fisherman will teach him all that he requires of these simple but extremely useful accomplishments.

The best food for sustaining life in the north is pemmican. It was once made out of buffalo meat, but now the flesh of the moose, or caribou, or of the deer, is substituted. The meat is cut in thin flakes and air-dried; then a mixture is made of one-third dried meat, one-third pure haunch fat, and one-third service berries (A. canadensis). These are rammed by main force into a bag of green hide, and pounded until as solid as a rock. Such a solid mass of food will keep for years in a cool climate.

Perhaps the reader may be inclined to exclaim: “Why so much about the North; why not more about the East, South or West?” My reply to such would be: Because the great finds of the future will surely be made in the North. Dr. G. W. Dawson, the best authority on the subject, has said there are 1,000,000 square miles of virgin territory in Canada to-day, and no doubt a very large proportion of it contains mineral deposits. This 1,000,000 square miles he divides into sixteen separate areas, some half as large as Ireland, others half that of Europe, and in none of them has the footfall of a white man yet been echoed.

Contact us to Start Your Own Gold Mine

Contact us to Start Your Own Gold Mine. There is a simple rule at Start Your Own Gold Mine: if we can help you, we do, whenever and wherever necessary, and it's the way we've been doing business since 2002, and the only way we know

Contact Mr. Jean Louis by ![]() Telegram at username

@rcdrun or by

Telegram at username

@rcdrun or by WhatsApp Business.

Or call Mr. Louis at +256706271008 in

Uganda or send SMS to +256706271008